Sdn. Bhd.” content_1=”We are Malaysia’s leading biomass supplier and specialist.” content_2=”We are a reputable supplier of biomass products in Malaysia with more than 10 years experience in the biomass trade. Started with providing customers with wood pelletizing equipment, we have expanded our operations to sourcing and procuring all sorts of biomass products for our customers.

“]

Malaysian territory is approximately two-thirds forest, but it is also home to many mangroves and peat forests. In 2010, Malaysia’s national forest cover was 20.46 million ha, about 62% of its total land area, and up from 56% in 2007. Unfortunately, within a year, Malaysia’s forested areas dropped to nearly 18.5 million ha (56.4% of land area).

The primary tree species in Malaysia are from the Dipterocarpaceae family, making Malaysia’s forests appropriately named “dipterocarp forests.” Despite such widespread forest cover, Malaysia’s forests have been devastated by unchecked logging activities. Reportedly, over 80% of Sarawak’s forests and over 60% of Peninsular Malaysia’s forests have been cleared. Today, most of Malaysia’s forested areas are still able to be found within its national parks.

Forests in Southeast Asia are relevant sources of timber and other forest products, local energy for cooking and heading, and potentially as sources of bioenergy. Many of these forests have experienced deforestation and forest degradation over the last few decades. The potential flow of woody biomass for bioenergy from forests is uncertain. It needs to be assessed before policy intervention can be successfully implemented in the context of international negotiations on climate change.

Using current data, we developed a forest land-use model and projected changes in the area of natural forests and forest plantations from 1990 to 2020. We also developed biomass change and harvest models to estimate woody biomass availability in the forests under the current management regime. Due to deforestation and logging (including illegal logging), projected annual woody biomass production in natural forests declined from 815.9 million tons (16.3 EJ) in 1990 to 359.3 million tons (7.2 EJ) in 2020. Woody biomass production in forest plantations was estimated at 16.2 million tons yr−1 (0.3 EJ) but was strongly affected by cutting rotation length.

The average annual woody biomass production in all forests in Southeast Asia between 1990 and 2020 was estimated at 563.4 million tons (11.3 EJ) yr−1 declining about 1.5% yr−1. Without incentives to reduce deforestation and forest degradation, and to promote forest rehabilitation and plantations, woody biomass, as well as wood production and carbon stocks, will continue to decline, putting sustainable development in the region at risk as the majority of the population depend mostly on forest ecosystem services for daily survival.

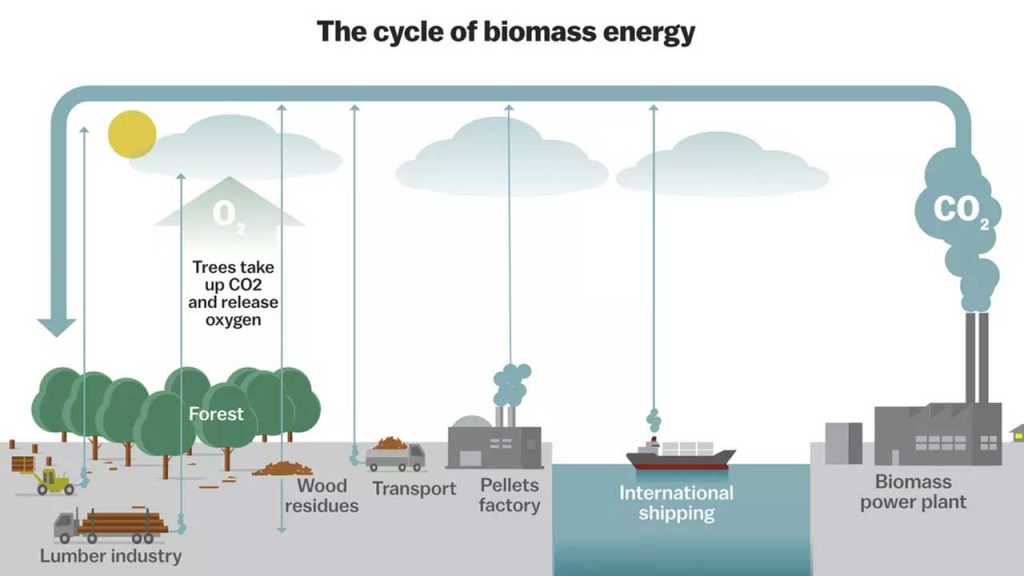

Biofuels are entirely different from fossil fuels in almost every possible way. As a generalization, solid biomass fuels are soft and fibrous products from plants that have been harvested recently as opposed to hard and brittle coal, which has been geologically deposited deep underground for over 50 million years (Fossil Fuel). Biomass tends to be produced on a much smaller scale than the extensive mining operations used to extract coal. Both the bulk density and the heat content per weight of biomass are considerably lower than for fuel. In contrast, the moisture content of fresh biomass is higher. All this means that transport and handling costs are a much larger part of the total cost of fuel.

The fact that the properties are so different means that equipment developed for the agricultural sector can sometimes be more suitable than power station equipment designed for coal. Although the biomass tends to generate dust that stays airborne longer than coal, it is not as dirty in the same way as coal dust. Most dry biomass needs to be stored under cover to avoid self-heating, decomposition, and growth of spores and fungi, although product development changes this situation. Thermally treated wood pellets that are much more hydrophobic are starting to enter the market. While they are more expensive to produce, they can be stored in the open, saving investment in undercover stores.

• Accountability – means accepting the obligations of our role in the company and accounting for our activities, maintaining our professional competence and delivering on the performance expectations of our clients and customers.

• Yielding – means ensuring a mutually beneficial and ethical business “code of conduct’, that reflects full transparency.

• Integrity – means being responsible and adapt to the changing business environment ensuring our services and product remain relevant to our clients and stakeholders.

• Networking – means continuously striving to deliver the covenant we have made with our clients and customers so that we meet our mutual obligations to each other.

“]